Editor’s note: Many businesses are closed as a result of the coronavirus pandemic, and some building managers have shut off water and air conditioning to conserve resources. Unfortunately, warmth and lack of clean water flow can contribute to the growth of potentially dangerous microbes, including the bacteria that contribute to Legionnaires’ disease. Illinois Sustainable Technology Center chemist and industrial water treatment specialist Jeremy Overmann spoke with News Bureau life sciences editor Diana Yates about the problem and potential solutions.

What are the potential sources of tainted water in an unoccupied building?

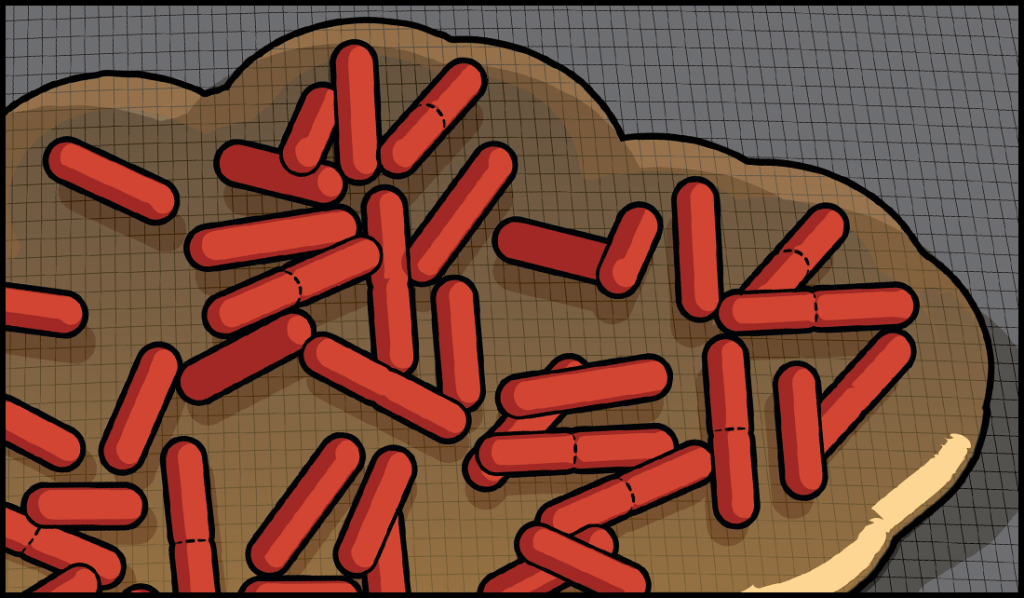

When a building is unoccupied, water stagnates in the building’s plumbing systems and the disinfectant (chlorination) dissipates. Bacteria can then multiply and form biofilms on the internal surfaces. Without regular use of water, the temperature in these systems may rise or fall into the range in which Legionella bacteria can grow. As a result, the hot and cold tap water systems – including storage tanks, ice machines, drinking fountains and water softeners – can become unsafe. Other potential sources of Legionella include sprinkler systems, decorative fountains, hot tubs, eyewash stations, safety showers, humidifiers and idle cooling towers.

How might these sources expose or infect returning workers?

If water containing Legionella is released from any of these systems in a manner that produces aerosol, mist or droplets, these can be inhaled and cause a serious, sometimes fatal pneumonia. Another route of exposure, though less likely, is aspirating contaminated water into the lungs while drinking. The symptoms of Legionnaires’ disease are the same as some of those from COVID-19 and could result in a misdiagnosis. Legionella does not cause harm when ingested, however other pathogenic bacteria might be present, which can cause infection by this route and even by skin contact.

What can building managers do now to minimize or eliminate the threat?

The American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers has written a standard that establishes minimum legionellosis risk management requirements for buildings with complex water systems. Standard 188-2018 directs building managers to assemble a water management team and write a water management program for the facility. If the facility has a WMP, managers should review it and meet remotely with the water management team.

The WMP should include protocols for maintaining safe water systems in unoccupied buildings. If none exist, the team might be able to develop them. Generally, hot and cold plumbing systems – including water softeners, equipment, storage tanks and all fixtures – need to be thoroughly flushed a minimum of once per week to remove stagnant water and replace it with water containing an adequate level of chlorination.

A water softener may be regenerated as an alternative to flushing. Drinking fountains should either be flushed regularly or shut off completely from the water supply. If they are shut off, the fountains must be cleaned according to the manufacturer’s instructions before being used again for drinking.

Ice machines should be disconnected from the water supply and stored according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Decorative fountains and hot tubs should be turned off, drained and stored dry. The same goes for humidifiers and cooling towers, if they are not needed. If still needed for cooling, the tower water circulating pump should be kept on continuously, water should be continually bled from the tower, and adequate biocides should be applied regularly to maintain control of biological growth.

What should water system operators do if they have already left their facilities idle for weeks?

Operators should consult the facility’s water management program, as it should contain protocols for start-up of water systems after shut-down or a period of nonuse. The water systems will likely need to be flushed, cleaned, disinfected and recommissioned. After being remediated, they should be tested to verify the safety of the water and the presence of adequate disinfectant.

Who can facility managers call on for advice, inspection or treatment of their tainted systems?

I recommend hiring a reputable water management consultant with experience remediating these types of systems. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has a guidance document containing relevant information for building water systems that is available on its website.

Editor’s note: To contact Jeremy Overmann, email joverman@illinois.edu.

This is the first in a periodic series of Ask Me Anything (AMA) posts where ISTC features a researcher on our Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn accounts and solicits questions from our followers. We post the answers on the original platform and also aggregate them into a wrap-up blog post. Our first featured researcher is

This is the first in a periodic series of Ask Me Anything (AMA) posts where ISTC features a researcher on our Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn accounts and solicits questions from our followers. We post the answers on the original platform and also aggregate them into a wrap-up blog post. Our first featured researcher is

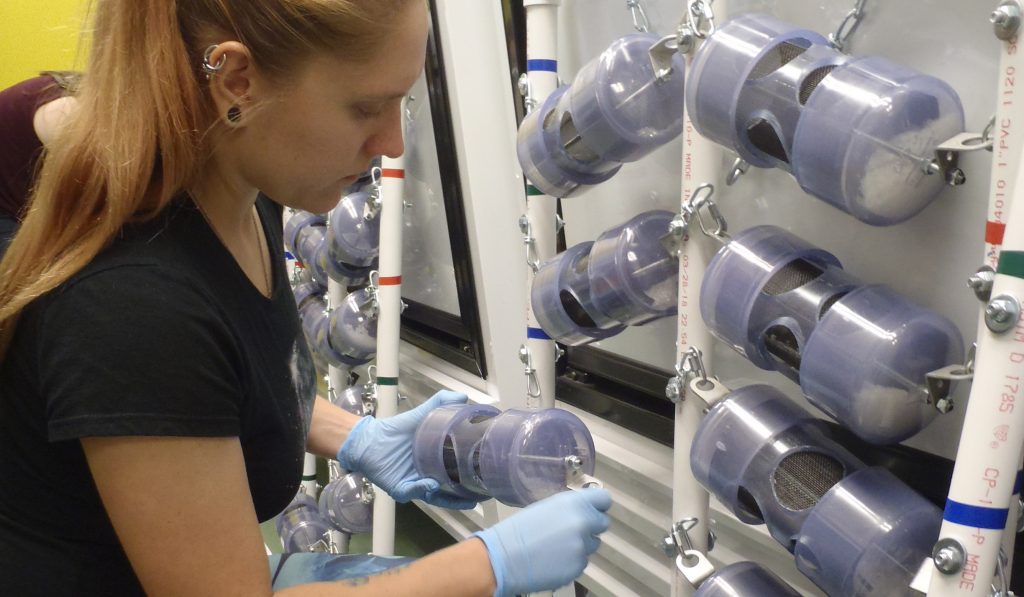

With funding from U.S. EPA, ISTC’s Technical Assistance Program (TAP) is working with the food and beverage manufacturing and processing sector to help them reduce their energy consumption, water use, hazardous materials use, and operating costs. Cleaning and sanitation is a critical process throughout the industry and is one that is ripe for improvement.

With funding from U.S. EPA, ISTC’s Technical Assistance Program (TAP) is working with the food and beverage manufacturing and processing sector to help them reduce their energy consumption, water use, hazardous materials use, and operating costs. Cleaning and sanitation is a critical process throughout the industry and is one that is ripe for improvement.