It hardly seems possible, but August is just around the corner, and for many K-12 schools and institutions of higher education in Illinois, that means it’s back-to-school season. Whether you’re a parent with a school supply list in hand, a college student preparing for a new semester, or just someone in the market for office supplies, the following suggestions can help you make more sustainable choices as a consumer.

Please note that ISTC does not endorse, either explicitly or implicitly, any manufacturer, brand, vendor, product, or service. Information about specific products, brands, manufacturers, or vendors is provided for reference only and should not be construed as an endorsement. Also, please be aware that this list of suggestions and alternatives to consider is by no means exhaustive and is meant simply to inspire you to be more intentional in your consumption and to consider the impacts of everyday items.

First, shop your own supplies & reuse/use up what you already have.

Parents of elementary-aged children will likely relate to the experience of kids cleaning out their lockers or desks at the end of a school year and bringing home partially used notebooks, used folders, pens, pencils, etc. While it’s possible that some items from the previous academic year are nearly worn out, or that these items might be used up over the summer for non-school activities, it’s also likely that at least some tools and supplies will still have useful life left when it’s time to begin a new school year. Designate a closet, shelf, or storage bin in your home or office to store school or office supplies that aren’t currently in use, so that when you need such supplies, you can quickly check your existing inventory and draw from it before you go shopping. Establishing this habit will save both money and the resources used to manufacture the supplies in question.

Shop for gently or never used supplies at a creative reuse center.

If the items you need aren’t part of your existing inventory, check to see if there is a creative reuse center in or near your community. These centers accept donations of supplies for art and education, as well as non-traditional materials that might be used for arts, crafts, school projects, lessons, and home décor, which would otherwise be sent to the landfill. These “non-traditional materials” might be hard-to-recycle items, or simply objects of visual or textural interest that might be transformed in a creative way. Examples of creative reuse include painting an old tin and using it as a planter, turning fabric scraps into a quilt, or making a collage from colorful buttons, bottle caps, or photos. Donations to creative reuse centers typically come from businesses, manufacturers, local institutions, and members of the general public. Such centers then resell the donated items for profit or to support charitable organizations or initiatives while reducing waste and encouraging reuse. Think of them as thrift stores focused on art and office supplies. Some donated items have never been used. Like checking your own inventory before buying new, shopping at creative reuse centers will not only conserve resources by ensuring products remain in use and out of landfills for as long as possible, but they also typically save consumers money as compared to shopping for brand new items. So, once you’ve checked your own inventory of supplies, check your community’s pool of supplies. Multiple creative reuse centers exist in Illinois. Champaign-Urbana is served by the Idea Store, while the WasteShed operates creative reuse centers in Chicago and Evanston. Chicago is also served by Creative Chicago Reuse Exchange (CCRx). SCARCE serves DuPage County and is in Addison, IL. Springfield residents can shop at the Creative Reuse Marketplace. Keep in mind that other resale shops and thrift stores might also have office supplies, so if your community doesn’t have a creative reuse center, you might still be able to find “new to you” supplies that would otherwise have been wasted. Creative reuse centers can be found throughout the U.S., so if you’re reading this from outside Illinois, do an Internet search for “creative reuse center + [name of your state].”

Choose refurbished devices and remanufactured ink and toner cartridges.

Continuing the theme of reusing existing products before buying new ones, if you’re in the market for a new laptop or other electronic device, consider searching for a certified refurbished device first. While you would be wise to think twice before purchasing “used” items from a complete stranger on a platform like eBay or Craigslist, certified refurbished items have been restored to “like new” condition and verified by technicians to be fully functional. Quality is thus not an issue. But because these items can’t be sold as new, they’re typically available at a discount when compared to genuinely new items. Another win-win for the conservation of resources and money! Many companies such as Best Buy, Dell, or Amazon make it easy for consumers to find refurbished devices in their online stores. The downside of shopping for refurbished tech is that you can’t guarantee you’ll find the exact model or item you’re looking for at the precise time you search; it depends on what is available.

There are also non-profit and for-profit organizations throughout the U.S. which refurbish electronics (typically donated) and resell them at a discounted price to individuals who might otherwise not be able to afford such equipment. These organizations address both social and environmental aspects of sustainability, helping to bridge the digital divide while extending the useful life of products and stemming the ever-growing tide of e-waste. Keeping these entities in mind is great if you or someone you know needs help obtaining a device, or, on the other hand, if you’d like to donate an older device so someone else can benefit from it. You’ll find that reputable businesses in this sector can provide certification of data destruction, so security need not be a concern. Some of these organizations include a job training program, enhancing their positive impacts on communities. Some may also provide electronics recycling services to businesses, responsibly recycling devices that can’t be reused, and refurbishing and redistributing those that can. REcompute began in Champaign-Urbana, IL, and has expanded to Danville, IL, Los Angeles, CA, and is coming soon to Atlanta, GA. PCs for People has ten locations in the U.S., including two in IL (Oak Forest and Belleville). Free Geek began in Portland, OR, and multiple communities in the U.S. and abroad have started their own independent Free Geek organizations. Repowered in St. Paul, MN, is another example.

Remanufactured ink and toner cartridges have been professionally cleaned, refilled, and tested, decreasing demand for the plastics and other materials used to create the cartridges themselves. Life-cycle assessments (LCAs) have even shown that remanufactured cartridges have lower environmental impacts than brand-new cartridges. And again, you’ll save money as well as resources by practicing reuse.

Choose items that are refillable.

If you must buy a brand-new item, look for options that will foster future reuse through refilling. The classic example (and the one most likely to be compatible with K-12 supply lists) is choosing a refillable fountain, gel, or ballpoint pen instead of a disposable one. There are plenty of examples of such pens, but one that also incorporates recycled content is Pilot’s B2P or Bottle 2 Pen. B2P is made from recycled beverage bottles, is available as a ball-point or gel roller, and uses the same ink refill cartridges (available in several colors) that work in several other Pilot pens. For more info, see https://pilotpen.us/FindBrand and select “Bottle 2 Pen B2P” from the drop-down menu. The pens are 86-89% recycled content depending on pen type; product descriptions for the ball points say they are 83% post-consumer recycled material.

Mechanical pencils are a similar refillable option that immediately comes to mind. Bic produces an example of a mechanical pencil with recycled plastic content.

Refillable notebooks give you the compact feel of a spiral-bound notebook, as compared to a bulky three-ring binder, but like binders, allow you to insert new pages as needed or rearrange the order of notes. Some examples include Kokuyo Binder Notebooks, Lihit Lab, Filofax, and Minbok.

Dry erase markers are even available in refillable versions, such as the Pilot V Board Master or those from Auspen. The Stabilo Boss is an example of a refillable highlighter. Permanent markers such as those from Pilot can be refilled. Refillable acrylic markers are also available from brands like Montana. Crayola also has a DIY Marker Maker set, but they unfortunately don’t sell a refill pack. However, these could conceivably be refilled with inks available from other companies.

Choose new items made from recycled materials and look for high PCR content.

If refillable options aren’t available or applicable to some supplies on your list, try to find options made from recycled materials. When comparing options, examine product labels and descriptions for the percentage of “post-consumer recycled” content or “PCR.” These are materials that have been used by consumers and collected via recycling programs, so when you buy a product with the highest amount of PCR you can, you are genuinely “closing the loop” and making recycling effective and economically feasible by helping to create market demand for recycled materials. You’ve probably read articles about materials collected for recycling that ultimately don’t get recycled because there’s a lack of market for the commodities. That sort of thing has led some community recycling collection programs to stop altogether or to stop accepting certain materials. But most of the time, if a recycling collection program accepts a material it’s because they have an outlet for it; it wouldn’t make sense to collect materials that couldn’t be sold. The best things you can do as a consumer is to keep recycling the proper materials accepted by your local program, keep items NOT accepted by your collection program out of your recycling bins (contaminants can indeed ruin batches of materials collected or harm equipment at waste sorting and processing facilities), AND whenever possible, buy items with PCR content. Note that if a product is described as having a certain percentage of recycled content but there’s no mention of PCR, it’s likely that the recycled content is post-industrial (aka pre-consumer) rather than post-consumer. That entails excess materials or trimmings from a manufacturing process used as feedstock for the creation of the same or different products without ever being used by a consumer first (e.g., cardboard trimmings repulped and put back into the process of making boxes). Odds are, if a company has successfully incorporated PCR into their products, they will want to point it out on the label or in the product description/details in online stores. This blog post from EcoEnclose provides a good overview of PCR vs. post-industrial content.

That said, here are just a few examples of common supplies made from PCR (besides those already mentioned above). You can find more by searching the Internet for “PCR content + [product].”

- Standard (non-mechanical) pencils can be made from recycled newspaper, like these from Amber and Rose.

- Decomposition notebooks, sketchbooks, and filler paper are made from 100% PCR paper. They also offer refillable ball-point pens made from 90% PCR plastic and three-ring binders made from 85% PCR plastic.

- Everyday Recycler provides this list of backpacks containing recycled plastic.

- 100% PCR printer paper is available, such as that from Printworks, AbilityOne, or Target.

- ACCO paper clips contain 90% recycled materials, 50% of which is PCR.

Hopefully, this has given you some ideas for considerations and criteria to keep in mind when looking for school and office supplies. There are certainly other product categories and other factors that can be considered (e.g. more renewable materials, plastic-free items, items manufactured with renewable energy, etc.), but the suggestions above are a great start. Students, good luck in your classes, and may everyone else be productive while also conserving resources!

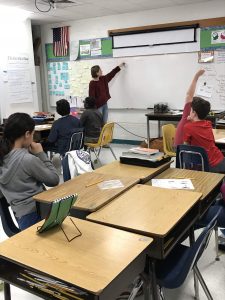

Amanda Price piloted the unit in two fifth grade science classes at Butler Elementary and Sandburg Elementary February-March 2020. Both schools are located in Springfield, IL. Amanda works as a Graduate Public Service Intern (GPSI) in the offices of Environmental Education and Community Relations at Illinois EPA. The

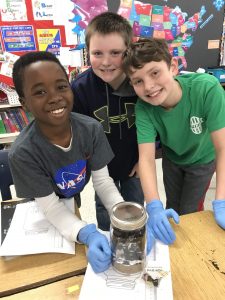

Amanda Price piloted the unit in two fifth grade science classes at Butler Elementary and Sandburg Elementary February-March 2020. Both schools are located in Springfield, IL. Amanda works as a Graduate Public Service Intern (GPSI) in the offices of Environmental Education and Community Relations at Illinois EPA. The  driven by student questions. It teaches students the importance of food waste reduction, landfill diversion, and composting as part of a circular food system. Students create “landfills in a jar” with materials given to them with the goal of protecting the sand, or “groundwater,” at the bottom of the jar. Students also create “compost in a jar” using fresh food scraps and other compostable materials. Students monitor their jars throughout the unit and record scientific data such as temperature and mass. They learn how bacteria act as decomposers. The unit also incorporates map-reading and asks students to think critically about the pros and cons of choosing space for new landfill construction.

driven by student questions. It teaches students the importance of food waste reduction, landfill diversion, and composting as part of a circular food system. Students create “landfills in a jar” with materials given to them with the goal of protecting the sand, or “groundwater,” at the bottom of the jar. Students also create “compost in a jar” using fresh food scraps and other compostable materials. Students monitor their jars throughout the unit and record scientific data such as temperature and mass. They learn how bacteria act as decomposers. The unit also incorporates map-reading and asks students to think critically about the pros and cons of choosing space for new landfill construction. The main hands-on activity in the unit is a food waste audit, which can be performed at various scales. Students use data from the audit to calculate the estimated food wasted per person, during the school year, etc. Students end the unit by creating a community awareness or action plan to inform their community or advocate for change. A few students at Butler Elementary wrote a letter to the principal asking him to install a clock in the cafeteria so students could track how much time they had to eat. The principal took swift action and ordered the clock.

The main hands-on activity in the unit is a food waste audit, which can be performed at various scales. Students use data from the audit to calculate the estimated food wasted per person, during the school year, etc. Students end the unit by creating a community awareness or action plan to inform their community or advocate for change. A few students at Butler Elementary wrote a letter to the principal asking him to install a clock in the cafeteria so students could track how much time they had to eat. The principal took swift action and ordered the clock. What’s the problem with food waste in schools?

What’s the problem with food waste in schools?