ISTC has announced its schedule of sustainability seminars for Spring 2019. All seminars are held from noon-1 pm in the SJW Conference room at ISTC 1 Hazelwood Dr in Champaign. Metered parking ($1/hr) in the lot; bike parking; and yellow bus stops at Hazelwood and Oak.

The seminars are also broadcast via webinar for those who can’t attend in person. Register for each session using the links below. Archives of previous seminars are available at https://www.istc.illinois.edu/events/sustainability_seminars.

Thursday, February 7

Recent Advancements in Virus Detection and Monitoring

Speaker: Krista Rule Wigginton, Assistant Professor

University of Michigan Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering

Register for the free webinar

Abstract: Viruses are important pathogens that are commonly associated with contaminated water. Norovirus, for example, is a waterborne virus that is responsible for 10x more illnesses in the U.S. than the next most common waterborne pathogen. To address risks of waterborne virus illnesses, drinking water standards include enteric virus reduction requirements; however the utility of these standards is limited in the absence of methods that can demonstrate they are achieved. Viruses are very difficult to concentrate, purify, and identify. Detection typically relies on culture-based or PCR-based methods; however, most viruses are not readily cultured, and their lack of conserved genes and rapid evolution complicates PCR primer development and sequencing efforts. In this presentation, I will report on our work focused on improving virus detection and monitoring in wastewater and drinking water.

Thursday, February 21

Materials, Assembly Approaches, and Designs for Ultrahigh-Efficiency, Full-Spectrum Operation Photovoltaics and their Applications

Speaker: Ralph G. Nuzzo , G. L. Clark Professor of Chemistry, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Register for the webinar

Abstract: The production of integrated electronic circuits provides examples of the most advanced fabrication and assembly approaches that are generally characterized by large-scale integration of high-performance compact semiconductor elements that rely on rigid and essentially planar form factors. New methods of fabricating micro-scale semiconductor devices provide a set of enabling means to lift these constraints by engendering approaches to device configurations that would be impossible to realize with bulk, wafer-scale materials while retaining capacities for high (or altogether new forms of) electronic and/or optoelectronic performance. An exemplary case of interest in our work includes large-area integrated electro-optical systems for photovoltaic energy conversion that can provide a potentially transformational approach to supplant current technologies with high performance, low cost alternatives. In this talk I will highlight progress made in the collaborative research efforts that illustrate important opportunities for exploiting advances in optical and electronic materials in synergy with physical means of patterning, fabrication, and assembly to advance capabilities for photovoltaic energy conversion and highlight emerging applications for new materials and unconventional device form factors in high efficiency energy conversion technologies. Of particular interest are the materials, and new understandings of science, that will allow an efficient utilization of the full solar resource.

Thursday, March 7

Removal of Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) from Water Using Tailored and Highly Porous Organosilica Adsorbents

Speaker: Paul Edmiston ,Theron and Dorothy Peterson Professor of Chemistry and Analytical Chemist, The College of Wooster (Ohio)

Register for the free webinar

Abstract: Porous organosilicas with specific surface chemistries were developed as adsorbents for the selective removal of either perfluoroalkyl surfactants (PFASs) from water. Swellable organically modified silica (SOMS) materials were created that incorporated cationic and fluoroalkyl groups with the hypothesis that intermolecular interactions specific to PFASs would improve adsorption affinity and capacity. SOMS materials are useful in adsorbent design since they possess: i) the ability to swell to creates a continuous mesoporous structure, ii) a surface chemistry that can be tailored through synthesis or incorporation of polymer coatings to the pores, and iii) chemical stability to allow for regeneration in place. Adsorption kinetics, adsorption isotherms, and column breakthrough experiments were used to measure performance for a range of PFASs with variable chain length and chemical identity (PFDA, PFNA, PFOA, PFHpA, PFHxA, PFOeA, PFBA, PFOSA, PFxHs, PFOSA, and PFOSaAm). Organosilica materials show promise for allowing rational design of adsorbents used for remediation of PFAS impacted water. Adsorption mechanisms unique to SOMS will be presented in the context of treatment of wide range of water solutes for those with general interest in water purification technology.

Thursday, March 28

Modern Materials: New Methods in Manufacturing and Remediation

Speaker: Adam M. Feinberg, postdoctoral researcher, University of Illinois Autonomous Materials Systems (AMS) Group

Register for the free webinar

Abstract: This seminar will discuss topics at the beginning and the end of the material lifecycle. At the beginning of the material lifecycle, a new material manufacturing method will be discussed – morphogenic manufacturing, i.e. the generation of pattern and structure without machining or molding. Unstable reaction propagation during frontal ring-opening metathesis polymerization (FROMP) of dicyclopentadiene (DCPD) has been harnessed to generate spatially-resolved patterns in pDCPD resins. Autonomous color pattern development, pattern characterization and tunability, and applications to real-world systems will be discussed. The second section of this talk will center on the end of the material lifecycle. Cyclic poly(phthalaldehyde) (cPPA), an attractive transient material which rapidly depolymerizes upon activation, has been used to produce transient bulk materials. Topics will include advances in bulk processing of cPPA, mechanistic insights learned along the way, and the future of this stimulus-responsive polymer.

Thursday, April 18

PFAS remediation at MSU‐Fraunhofer: Electrochemical destruction in wastewater and landfill leachates using boron‐doped diamond electrodes

Speaker: Cory A. Rusinek – Scientist, Michigan State University‐Fraunhofer USA, Inc. Center for Coatings and Diamond Technologies

Register for the free webinar

Abstract: Boron‐doped diamond (BDD) electrodes have shown promise over the last decade for contaminant degradation with a number of studies showing its ability to degrade PFASs. The BDD material provides a combination of rigidity, high oxygen over‐potential, and overall electrode lifetime, which makes it an attractive option for an electrochemical treatment system. This presentation will cover the basic and applied research findings of using electrochemical oxidation (EO) with BDD electrodes to destroy PFAS in wastewater and other complex samples such as landfill leachates and wastewaters. Various complimentary treatment technologies for PFAS remediation will also be addressed.

ISTC was one of several expert organizations invited to provide information on microplastics at a public meeting hosted by

ISTC was one of several expert organizations invited to provide information on microplastics at a public meeting hosted by  The

The  Pharmaceuticals and other emerging contaminants in the environment are a growing cause for concern. One particular issue is the increase in antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Agriculture is often noted as a source of excessive antibiotic use. Over 70% of all antibiotics produced in the U.S. are used in animal agriculture. Overuse can encourage the selection of antibiotic-resistant genes (ARG).

Pharmaceuticals and other emerging contaminants in the environment are a growing cause for concern. One particular issue is the increase in antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Agriculture is often noted as a source of excessive antibiotic use. Over 70% of all antibiotics produced in the U.S. are used in animal agriculture. Overuse can encourage the selection of antibiotic-resistant genes (ARG).

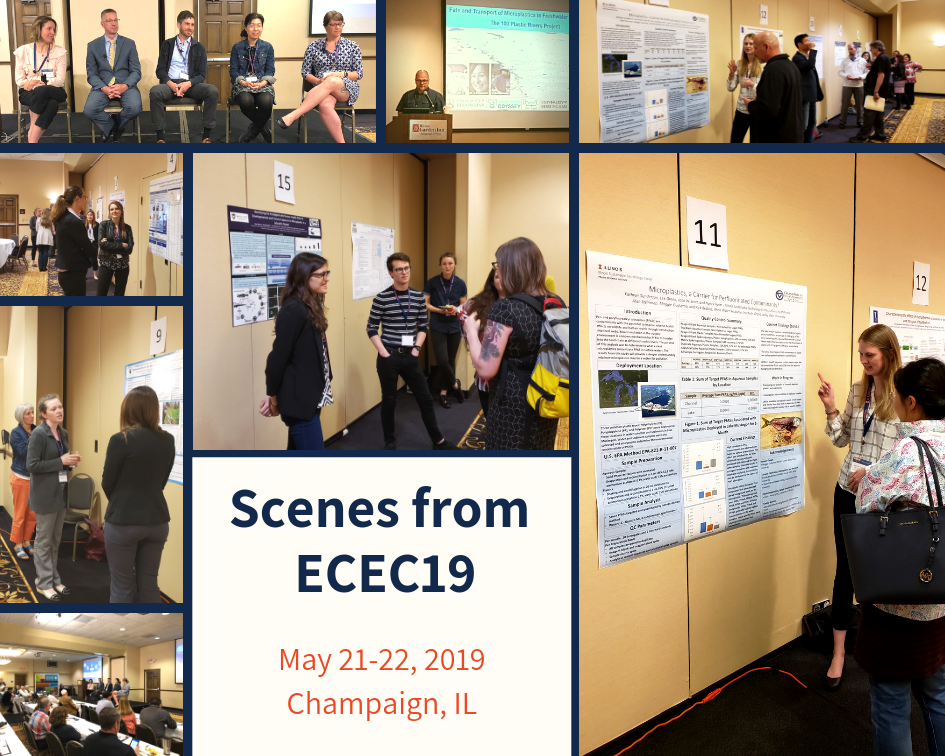

Join us on May 21-22 for the

Join us on May 21-22 for the