ISTC researchers John Scott, Beth Meschewski, and Lee Green traveled to the United Kingdom (UK) during the first week of February to discuss emerging contaminant issues with their international collaborators.

ISTC is one of six universities/organizations from U.S., UK, and France in an international working group called the International Freshwater Microplastics Network to reduce microplastics pollution in freshwater environments. The group met February 4-5, 2020, in a retreat meeting house on the campus of the University of Birmingham, UK. They shared information about recent projects, and then discussed the future of microplastics research.

ISTC is one of six universities/organizations from U.S., UK, and France in an international working group called the International Freshwater Microplastics Network to reduce microplastics pollution in freshwater environments. The group met February 4-5, 2020, in a retreat meeting house on the campus of the University of Birmingham, UK. They shared information about recent projects, and then discussed the future of microplastics research.

The group agreed that writing yet another review paper on the status of microplastics in the environment and the research being done was NOT an effective strategy. Instead, they proposed several concrete research ideas, settling on pooling individually collected microplastics data to help develop more robust contamination models for both local and global scenarios. However, most studies report number of particles per volume of water sampled, but current models require an input of mass of plastic per unit volume. To address this issue, the group also wants to standardize the methods used for collection, analysis, and reporting.

While at U of Birmingham, they met with other colleagues to discuss methods development for the detection of various emerging contaminants. They are particularly interested in how emerging contaminants are taken up, transported, and re-released by microplastics.

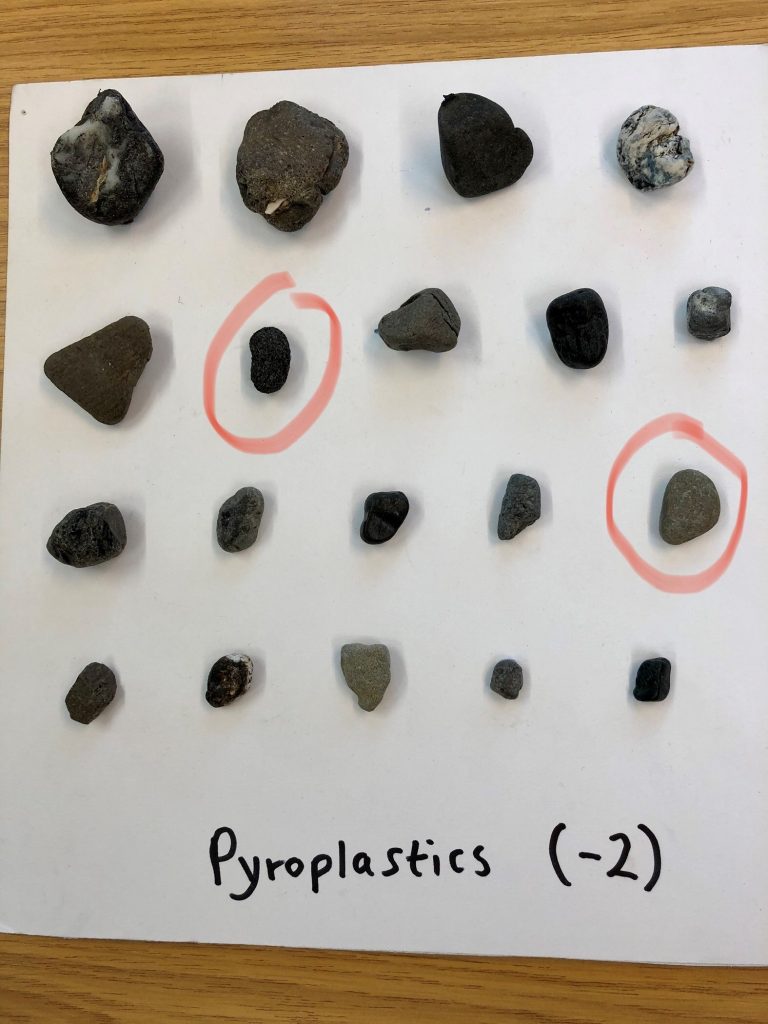

The three ISTC scientists also visited the University of Plymouth to meet with a colleague working on marine plastic and additives associated with plastics. The Plymouth research group created a display board of 18 materials collected on beaches in the UK, only two of which were natural materials. The remainder were all plastic “rocks” that look very much like natural rocks. ISTC scientists found it difficult to identify two natural rocks just by looking at them. However, there was an obvious weight difference between similarly sized plastic and natural rocks once they picked them up.

The ISTC team and the leader of the Plymouth research group spent some time analyzing black plastics by X-ray fluorescence. This method of analysis can determine the bulk elemental composition of these materials down to the part-per-million (ppm) range. Many of the samples tested contained very high concentrations (in the percent level) of bromine and antimony. If these two elements are present in plastics, it may indicate that the material was sourced from electronic waste. ISTC researchers collected several of these black  plastics from the U of Plymouth group to analyze them for rare earth and precious metals. The rare earth and precious metals may be present at low concentrations (ppt-ppb) in the plastics if they were sourced from electronic waste. Black plastic is increasingly used in a wide range of products that can include electronics, food containers, packaging, construction materials, textiles, and so on. Many of the metals and additives associated with these materials are toxic to humans, so recycling of these plastics has the potential to increase human exposure to pollutants.

plastics from the U of Plymouth group to analyze them for rare earth and precious metals. The rare earth and precious metals may be present at low concentrations (ppt-ppb) in the plastics if they were sourced from electronic waste. Black plastic is increasingly used in a wide range of products that can include electronics, food containers, packaging, construction materials, textiles, and so on. Many of the metals and additives associated with these materials are toxic to humans, so recycling of these plastics has the potential to increase human exposure to pollutants.

The ISTC team believes that the four new research projects discussed during the trip will make a significant impact in reducing emerging contaminants pollution at the international level.